Crude oil and natural gas sector is a main economic sector in Colombia, so there is huge historical and financial work about it. This work has been dealt by researchers from local universities, government bodies and foreign researchers also. However, there is a topic on crude oil and natural gas that has not been dealt still; it is the crude oil and natural gas perspective from Foreign Direct Investment view. Therefore, this note and my next weekly note will fill this gap. Contributions through this methodology is a complete data series of FDI in crude oil and natural gas sector in Colombia since 1894 and, in contradiction of previous works that point the FDI in crude oil sector as the main one through the first half of XX, I will point that this FDI shows cycles according to international economic scenario and local legislation. Of course FDI as stock in crude oil sector in Colombia reached 47.1% of total FDI as stock in 1928, but it was the peak of the first cycle.

Author: Humberto Bernal,

Economist,

Twitter: Humberto_Bernal

Colombia is a small country that economically depends of commodities such as coffee beans, bananas, gold, silver, emeralds, flowers, coal, ferronickel and crude oil mainly; therefore, there are important works about these commodities. In crude oil and natural gas topic important researchers such as universities and government bodies have broadcasted historical and financial information about it. However, these works did not work this sector (crude oil and natural gas) from inflows of Foreign Direct Investment view, so there is a gap that this note and the next one will fill. The FDI in crude oil sector can be divided into three periods: from 1894 to 1950; from 1951 to 2002 and from 2003 to nowadays. This first note will work FDI in crude oil sector in Colombia from 1894 to 1950, and my next week note will work the next periods. I will take FDI in crude oil sector as FDI in both crude oil and natural gas sector; the natural gas investment took relevance since 1960.

The first period of these three is taken because the type of crude oil production was through concession type. The second one was through association between government and private firms; and the final one is concession type where government firms can take part.

The first period of this FDI in crude oil sector in Colombia is interesting because Colombia did not have crude oil legislation until 1931, but the exploration started at the end of XIX century; moreover, production in high volumes started in 1921 and Colombia started to export this crude oil in 1926. Therefore, fields where crude oil was discovered were managed according to mining legislation and royalties were set up according each field before 1931. Other interesting issue is people use to say that FDI in crude oil sector through this first period was the main one as Twomey (2000) says Pag. 170, but it is not true at all; FDI as stock in crude oil sector in Colombia went from 0.2% of total FDI as stock in 1900 to 47.1% in 1928 and 32.4% in 1951; therefore, there were other activities that took foreigner firms attention such as gold and silver mines, bananas, coffee trade, beer, sugar, metallurgy, textiles, spirits and others consumption goods trade, hotels, banks and public services (public utilities).

Time Line for Foreign Direct Investment in Crude Oil in Colombia

The discovery of crude oil in Colombia comes back to XVI century when the Spanish conqueror Gonzalo Jiménez de Quesada reported that this black liquid was taken by indigenous for shielding their boats, as energy for their fires and as medical purposes. This black liquid was discovered in Middle Valley of Magdalena River and is was called the Infantas’ well. After this date, there were other discoveries such as the well that belonged to Colonel Drake Titusville; it was in middle of XIX century. There was other discovery in Barranquilla city in 1883 that was called Tubará; this project was supported by local and foreign firms through french Luis Striffler; this french had an interesting history in Colombia see Hombre Hicotea(1992) documentary; Turbará well had a productivity of 50 barrels per day as Asociación Americana de la Indistria del Petróleo(2013) says.

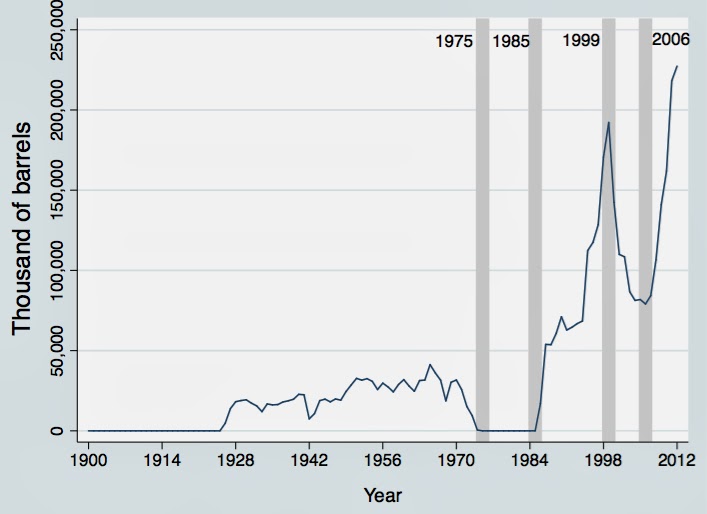

Figure 1. Foreign Direct Investment Inflows in Crude Oil and Natural Gas sector Colombia

(US$ million in 2012 prices)

The first FDI in crude oil registered was in 1894. At the end of XIX century (1880) Jorge Isaac the writer that wrote Maria novel had a crude oil concession in Urabá region (Atlantic Coast) that sold to american firm Panamerican Investment; this concession was sold to this american company in US$40 thousand in 1894 (US$1.1 million in 2012 prices).

There were small investments before De Mares concession (Infantas well belonged to De Mares concession). At the beginning of XX century (1909) Colombia counted with her first crude oil refinery called Cartagena Oil Refining Co that refined 400 barrels of crude oil imported. By 1911, the Standard Oil from New York decided to do a join venture with Diego Martínez with a total investment of US$90 thousand (US$2.2 millions in 2012 prices). In 1914, this american company and Martínez decided to increase their investment to explore the Sinú region with US$750 thousand (US$17.1 million in 2012 prices); unfortunately their results were disappointed. The total FDI as stock in crude oil sector in Colombia was US$2.0 million in 1914 (US$46 million in 2012 prices) see Lewis (1938) and Ecopetrol (2011).

The beginning of important crude oil production in Colombia was after 1916 through two foreign firms mainly. The first one was the american Compañia de Petróleo de Colombia that arrived in 1917, and it made an investment of US$100 thousand in 1917 (US$1.8 million in 2012 prices); this company was known as Texaco-Mobile multinational years after. The other one was the american Tropical Oil that arrived in 1916.

An important year for crude oil sector in Colombia was 1919. The concession called Concesión De Mares (Infantas’s well) was bought by three americans through Tropical Oil Company in US$1.5 millions (US$20 million in 2012 prices) and there was an important investment of US$1.0 million (US$13.3 million in 2012 prices) by the Andian National Corporation Limited from Canada to make a crude oil pipe to transport crude oil from Barrancabermenja region (where Concesión De Mares is located) to Cartagena port and to make a refinery in Barrancabermenja. It is import to highlight that the Tropical Oil was bought in US$100 million in 1920 (US$1,327 million in 2012 prices) by Standard Oil from New Jersey, but this transaction was between foreign people; therefore, this transaction can not be taken as FDI into Colombia; moreover, the Andian National Corporation from Canada was a branch of Standard Oil from New Jersey also; the Standard Oil from New Jersey broke their company in order to avoid legal issues that could bring more costs in Colombia. After many investments from americans, the total FDI as stock in crude oil sector in Colombia was US$ 20 million in 1919 (US$285 million in 2012 prices) see Lewis (1938) and Ecopetrol (2011).

After 1919 Colombia started her high production of crude oil. Colombia went from a production 50 barrels per day in 1883 to 200 in 1921 and 17.6 thousand in 1926; moreover, Colombia started to export crude oil in 1926 with a volume of 12.9 thousand of barrels per day see López et la (2012). To achieve this production the foreign firm International Petroleum Company that was the multinational that controlled the Tropical Oil, Andian National Corporation Limited from Canada and Standard Oil from New Jersey invested about US$35 million between 1920 to 1924 (US$470 million in 2012 prices); this investment went to produce crude oil, to transport it and to refine it; moreover in 1925 the Andian National Corporation Limited invested other US$15 million (US$196 million in 2012 prices) to complete the pipe line between Barrancabermeja and Mamonal (Cartagena). By 1929 the total FDI as stock in crude oil sector in Colombia was US$136 million (US$1,835 million in 2012 prices) see Lewis (1938) and Ecopetrol (2011).

Figure 2. Foreign Direct Investment Stock in Crude Oil and Natural Gas sector Colombia

(US$ million in 2012 prices)

Unfortunately, the economic crisis in 1929 and the Second World War brought a reduction of crude oil companies’s capital in Colombia; moreover, the flows of foreign capital in this sector was null until 1939. By 1935 the FDI as stock in crude oil sector in Colombia showed a reduction to reach US$126 million (US$1,668 million in 2012 prices) see Lewis (1938). This reduction was because of lower demand of crude oil and the average crude oil price showed a decline from US$1.6 per barrel between 1920 and 1929 (US$21.3 in 2012 prices) to US$1.0 per barrel between 1930 and 1939 (US$15.8 in 2012 prices).

Nonetheless, between 1940 and 1946 there was a huge FDI in crude oil sector in Colombia because of competition increased and the higher demand of crude oil by the United States and United Kingdom for their war machinery. As foreign firms from the United States, the United Kingdom and Germany realised that Colombia had important reserves of crude oil at the beginning of XX century, so they decided to come through few engineers to explore. However, from 35 firms that sent engineers between 1894 and 1930, there were three that got successful results. Some of these 35 foreign firms where Weetman Person, Shell and British Petroleum from the United Kingdom; Standard Oil and Texas Petroleum from the United States and few Germans that explored La Guajira and Urabá (Atlantic Coast) as Rippy (1976) and Ecopetrol (2011) pointed. The three foreign firms that got a success were Standard Oil and Texas Petroleum from the United Staes and Shell from the United Kingdom-Netherlands. The total FDI as inflow between 1940 and 1946 was US$66 million (US$847 million in 2012 prices); in terms of FDI as stock this volume was US$192 million between 1894 and 1946 (US$2,515 million in 2012 prices). Each of these three firms started to produce crude oil as follow: Standard Oil New Jersey through De Mares (Santander) concession in 1921; Standard Oil New York through Barco (Norte de Santander) concession in 1940; Shell through Yondó (Antioquia), Cantagallo (Bolívar) and El Difícil (Magdalena) concessions in 1941, 1943, 1943 respectively; and Texas Petroleum through Velásquez (Boyacá) concession in 1946.

The end of this first part of crude oil FDI shows a decline because of changing of crude oil legislation in Colombia. The main firm that produced crude oil in Colombia was Standard Oil from New Jersey with 75% of total production in 1950; moreover, the total reserves of crude oil in Colombia was 1,269 million of barrels in 1950, and most of them came from De Mares concession. However, this concession finished in 1951, and these reserves were taken by government firm called Ecopetrol; therefore the age of the government state as supplier of crude oil started. This government movement brought outflows of FDI in crude oil sector in Colombia; in 1950 and 1951 this sector faced an outflow of US$29 million each year (US$276 million in 2012 prices each year); therefore, the total FDI as stock in crude oil sector was US$134 million in 1951 (US$1,983 million).

Bibliography

Ecopetrol. 2011. Energía limpia para el futuro. Villegas Editores. Chapter 1, 2 and 3.

Lewis, C. 1938. American's Stake in International Investments. The Brookings Institution. Pag. 583 and forward.

López, E; Montes, E; and Collazos, M. 2012. La economía petrolera en Colombia Parte I. Banco de la República Colombia, documento de trabajo 692. Pag. 85.

Reppy, F. 1976. The Capitalists and Colombia. Arno press, New York. Pag. 249.

Towmey, M. 2000. A century of Foreign Investment in the third World, Routledge, London and New York. Pag. 170.